Oxford-AstraZeneca Vaccine

The not-for-profit Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is an example of a ‘vector vaccine’, which contains a reconstructed version of a different, harmless virus than the one that causes COVID-19. This vaccine does not contain any live SARS-CoV-2 virus, and cannot give you COVID-19. It contains a modified genetic code for an important part of the SARS-CoV-2 virus called the ‘spike protein’. This code is inserted into a harmless common cold virus (an adenovirus), which brings it into your cells. Your body then makes copies of the spike protein, and your immune system learns to recognise and fight the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The adenovirus has been modified so that it cannot replicate once it is inside cells. This means it cannot spread to other cells and cause infection.

Scientists began creating viral vectors in the 1970s. Alongside their use in vaccination technologies, viral vectors have also been studied for gene therapy, to treat cancer, and for molecular biology research. For decades, hundreds of scientific studies of viral vector vaccines have been completed and published worldwide. Some vaccines recently used for Ebola outbreaks have used viral vector technology, and a number of studies have focused on viral vector vaccines against other infectious diseases such as Zika, influenza, and HIV.

More information on vector vaccines may be found at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/viralvector.html

Safety and Effectiveness of the Oxford-AstraZeneca Vaccine

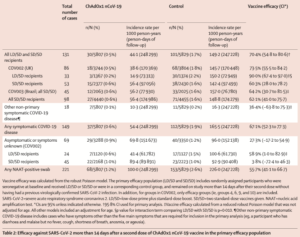

A study published in January of this year tested the safety and efficacy of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine on 23, 848 participants, 11,636 of whom were included in the interim primary efficacy analysis. The study was funded by: UK Research and Innovation; National Institutes for Health Research (NIHR); Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Lemann Foundation; Rede D’Or, Brava and Telles Foundation; NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre; Thames Valley and South Midland’s NIHR Clinical Research Network, and; AstraZeneca.

The research includes data from four ongoing blinded, randomised, controlled trials performed across three countries: the UK; Brazil, and; South Africa. Each of the four studies included participants who had received two doses, and a booster was incorporated into three of the trials that were initially designed to assess the safety and efficacy of a single-dose of the immunisation.

The research includes data from four ongoing blinded, randomised, controlled trials performed across three countries: the UK; Brazil, and; South Africa. Each of the four studies included participants who had received two doses, and a booster was incorporated into three of the trials that were initially designed to assess the safety and efficacy of a single-dose of the immunisation.

This analysis showed the overall efficacy of the vaccine was 70.4% in preventing symptomatic laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 in people aged over 18 years 15 or more days following the second dose in the primary efficacy study population.

Oxford-AstraZeneca was determined to have a good safety profile, with any adverse events (serious and non-serious) being balanced across the study arms. Out of the 23,848 participants, serious adverse events occurred in 168 participants, 79 of whom received the vaccine and 89 of whom received the placebo.

Source: Voysey et al. (2021) ‘Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK’ The Lancet, accessible at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32661-1/fulltext

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd.

A study pre-printed (not yet peer-reviewed) in April of this year researched the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccination in preventing COVID-19 in the community on 373,402 participants aged over 16 years though a UK population-representative longitudinal COVID-19 Infection Survey. The study was funded by: the Department of Health and Social Care with in-kind support from the Welsh Government; the Department of Health on behalf of the Northern Ireland Government, and; the Scottish Government.

The results of large randomised trials found that two doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was effective in 70% of cases against confirmed COVID-19 infection amongst the sample.

Source: Pritchard, et al. (2021) ‘Impact of vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 cases in the community: a population-based study using the UK’s COVID-19 Infection Survey’ medRxiv, accessible at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.22.21255913v1.full.pdf+html

For more studies on the safety and effectiveness of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccination, see list below:

• Mahase (2021) ‘AstraZeneca vaccine: Blood clots are “extremely rare” and benefits outweigh risks, regulators conclude’ British Medical Journal, accessible at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n931

• Bernal et al., ‘Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case-control study’ British Medical Journal, accessible at: https://www.bmj.com/content/373/bmj.n1088

• Emary, et al. (2021) ‘Efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/01 (B.1.1.7): an exploratory analysis of a randomised controlled trial’ The Lancet, accessible at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)00628-0/fulltext

• World Health Organization (WHO) (2021) ‘AZD1222 vaccine against COVID-19 developed by Oxford University and Astra Zeneca: Background paper (draft)’, accessible at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-AZD1222-background-2021.1

• Vasileiou, et al. (2021) ‘Effectiveness of first Dose of COVID-19 Vaccines Against Hospital Admissions in Scotland: National Prospective Cohort Study of 5.4 Million People’ The Lancet, accessible at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3789264

Risks of Vaccination

Common side effects after being administered the Oxford-AstraZeneca include: injection site pain or tenderness, tiredness, headache, muscle pain, and fever and chills. Most side effects are mild and temporary, going away within 1-2 days.

In December of last year, a study was published on the safety and immunogenicity of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. The data was gathered from the second phase of the clinical trials, which was a single-blind, randomised, controlled study of healthy adults aged over 18. There were a total of 560 participants and they were separated into subgroups by age (18-55, 56-69, and 70+).

For participants aged between 18-55 years:

• Injection site pain recorded an 61% frequency after dose 1 and a frequency of 49% after dose 2.

• Injection site tenderness recorded a 76% frequency after dose 1 and a frequency of 61% after dose 2.

• Fatigue recorded a 76% frequency after dose 1 and a 55% frequency after dose 2.

• Headaches recorded a 65% frequency after dose 1 and a 31% frequency after dose 2.

• Muscle pain recorded a frequency of 53% after dose 1 and a 35% frequency after dose 2.

• Fever recorded a 24% frequency after dose 1 and a 0% frequency after dose 2.

For participants aged between 56-69 years:

• Injection site pain recorded an 43% frequency after dose 1 and a frequency of 34% after dose 2.

• Injection site tenderness recorded a 67% frequency after dose 1 and a frequency of 59% after dose 2.

• Fatigue recorded a 50% frequency after dose 1 and a 41% frequency after dose 2.

• Headaches recorded a 50% frequency after dose 1 and a 34% frequency after dose 2.

• Muscle pain recorded a frequency of 37% after dose 1 and a 24% frequency after dose 2.

• Fever recorded a 0% frequency after dose 1 and a 0% frequency after dose 2.

For participants over 70 years:

• Injection site pain recorded an 20% frequency after dose 1 and a frequency of 10% after dose 2.

• Injection site tenderness recorded a 49% frequency after dose 1 and a frequency of 47% after dose 2.

• Fatigue recorded a 41% frequency after dose 1 and a 33% frequency after dose 2.

• Headaches recorded a 18% frequency after dose 1 and a 18% frequency after dose 2.

• Muscle pain recorded a frequency of 37% after dose 1 and a 24% frequency after dose 2.

• Fever recorded a 0% frequency after dose 1 and a 0% frequency after dose 2.

Source: Ramasamy, et al. (2021) ‘Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial’ The Lancet, accessible at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32466-1/fulltext

Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (TTS)

TTS is a rare event involving serious blood clots with a low blood platelet count. It is triggered by the immune system’s response to the AstraZeneca vaccine and is different from other clotting conditions.

Tragically, there have been 90 cases (54 confirmed, 36 probable) that have been correlated with the administration of Oxford-AstraZeneca and a total of 5 deaths. However, what must be kept at the forefront of our minds when considering these figures is that 6.3 million doses of the vaccine have been administered so far. This means that there is a 0.0014% chance of developing TTS from the Oxford-AstraZeneca and a 0.00008% from dying from it. You can access the COVID-19 Weekly Safety Report from the Therapeutic Goods Administration here.

According to the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, among the over 20 million people that have received the AstraZeneca vaccine in the United Kingdom, a mere 79 cases of rare blood clots have been recorded and 19 deaths. This is the equivalent of one case per 250,000 people (0.0004%) and a single death out of every one million vaccinated with Oxford-AstraZeneca.

Source: Wise (2021) ‘Covid-19: Rare immune response may cause clots after AstraZeneca vaccine, say researchers’ The Lancet, accessible at: https://www.bmj.com/content/373/bmj.n954.short?casa_token=SXtGwYH5U-QAAAAA:vuOJm0IRQ1SS1vJLgxjzyP2KtRalMAhus2WzOkNKHFGJor1oFf4uDdglUJqn96scdf5BOoeH9eXG

You are far more likely to develop blood clots from COVID-19. The development of a condition called ‘thrombocytopenia’ (a condition in which you have a low blood platelet count, which can lead to clotting) has been reported to be present in up to 41% of positive patients, with the figure rising to up to 95% in those with severe disease.

Source: Xu, Zhou & Xu (2020) ‘Mechanism of thrombocytopenia in COVID-19 patients’ Annals of Hematology, accessible at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7156897/